The Futurists, as their name implies, wanted to focus on creating a unique and dynamic vision of the future with artists incorporating images of urban landscapes and modern machinery into their work including trains, cars and aeroplanes. Their work encompassed a variety of artforms including painting, sculpture, architecture, theatre and music with an emphasis on violence, speed and the working classes. The movement was in effect a celebration of the machine age, with a deliberately provocative tone.

The Futurists were based primarily in Italy and were lead by the charismatic poet Filippo Marinetti who produced in 1908 the manifesto below;

“We want to fight ferociously against the fanatical, unconscious and snobbish religion of the past, which is nourished by the evil influence of museums. We rebel against the supine admiration of old canvases, old statues and old objects, and against the enthusiasm for all that is worm-eaten, dirty and corroded by time; we believe that the common contempt for everything young, new and palpitating with life is unjust and criminal.”

Dynamism Of A Dog On A Leash, 1912, oil on canvas, 90 cm 110 cm

The movement was at it’s most active in the years 1909-14 and influenced the thinking of some artists in Britain (hence the Vorticists). The depiction of movement or dynamism lay at the heart of much Futurist work, and artists developed some novel techniques to express speed and motion including blurring, repetition, and the use of lines of force. And here, they adopted methods employed by the cubists. This brings me to the work of Giacomo Balla.

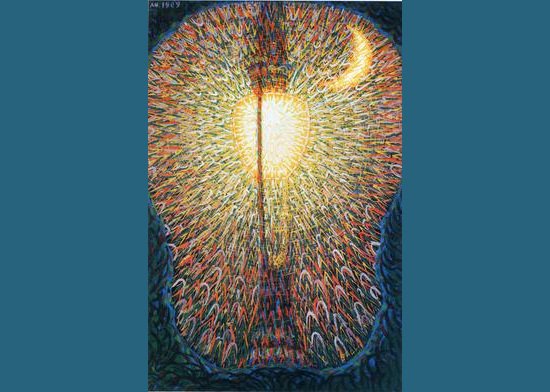

Balla was born in Turin in 1871 and is thought to have had little formal training in art. He moved to Rome in his early 20s and gradually came under the influence of Marinetti. Unlike most Futurists though, Balla was a lyrical painter and seemed less concerned with modern machines or violence. His 1909 painting “Street Light - A Study of Light” is a dynamic depiction of light. Futurism’s fascination with the urgency and energy of modern life is evident in this work.

Street Light, 1909, oil on canvas, 175 cm x 115 cm

In 1912 Balla produced “Dynamism Of A Dog On A Leash”, a playful exploration in the depiction of movement. The influence of cubism is thought to be evident in this painting. Reference has also been made to the principle of simultaneity in this work, that is; the rendering of motion by simultaneously showing many aspects of a moving object.

During the First World War, Balla produced a number of abstract works in which he further explored the depiction of speed through the use of planes of colour. These paintings are the most abstract of any produced by the futurists. The exploration into the optical possibilities of photo-scientific research carried out by Eadweard Muybridge and others were also thought to be influential in the work of Balla. This research gave Balla the opportunity to study the true nature of movement. The French impressionist Edgar Degas was also heavily influenced by Muybridge’s work.

Abstract Speed & Sound, 1914, oil on board, 55 cm x 77 cm

The horrors of the First World War saw many artists turn away from the ideals of Futurism. In his series “A History Of British Art” the art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon makes reference to the ‘machine gun’ philosophizing of the Vorticists and their joyful celebration of 20th Century technology. He believes this worshiping of the modern and the streamlined was eventually to be seen as a hollow pose due to WW1. “How can you celebrate technology when in war it can so effortlessly turn the human face into a bloodied abstract.”

Abstract Speed - The Car Has Passed, 1913, oil on canvas, 50 cm x 65 cm

The Futurist artists Umberto Boccioni and Antonio Sant’Elia both died in military service during WW1 and the influence of Futurism as a force in contemporary art waned after the conflict. However, Balla remained true to the early principals of Futurism (without the violence) and later in his career returned to more figurative work. He also designed futurist furniture and “anti-neutral” clothing. He died in 1958.

References;

The Art Story

A History of British Art - BBC TV

Brittanica.com

Wikipedia